How to keep our communities safe from wildfires

For residents of wildfire-prone communities: Why rapid initial attack is the wave of the future for wildfire suppression

On May 21, 2020 at about 5pm local time, the Michigan Department of Natural Resources received a report of a wildfire in Crawford County. In just a few hours, the fire, called M-72, had sprawled across more than 100 acres, plowing through a forest and threatening dozens of homes and structures. Four hours after the fire was reported and forced the evacuation of about 75 families, the blaze had been completely contained and the evacuation order reversed. A fire that could have evolved into a giant disaster had been controlled. Not a single life or home was lost. The story of the M-72 fire is a story of rapid initial attack.

Rapid initial attack is a simple concept: Put out unwanted wildfires fast and early, before they have the chance to grow into larger, harder to contain disasters, which threaten human life, damage homes and businesses and cost millions of dollars to suppress and recover from.

The strategy behind this concept is equally simple: Rapid initial attack is like the sprinkler system in an office building or local school. As soon as smoke is detected, the pre-installed sprinklers go off, rapidly and continuously drenching the environment with water until firefighters can arrive to put it out.

As with a sprinkler system, rapid initial attack requires upfront installation: At the start of a wildfire season, firefighting aircraft and helicopters are installed throughout a fire-prone region--pre-positioned and ready to spring into action at the first detection of wildfire smoke.

Like a sprinkler system, rapid initial attack aims for full coverage of an at-risk area, meaning aircraft and helicopters are systematically spread throughout a region so a firefighting asset can get to any of the region’s wildfires within an hour of being called in to help.

Once at a wildfire, water-scooping aircraft and helicopters that are built for rapid attack continuously bombard a fire with water by traveling back and forth between the fire and a nearby water source, scooping and dropping loads of water for multiple hours without having to travel back to a base, land, refill and take off again for the fire.

The US is built for rapid initial attack against wildfires.

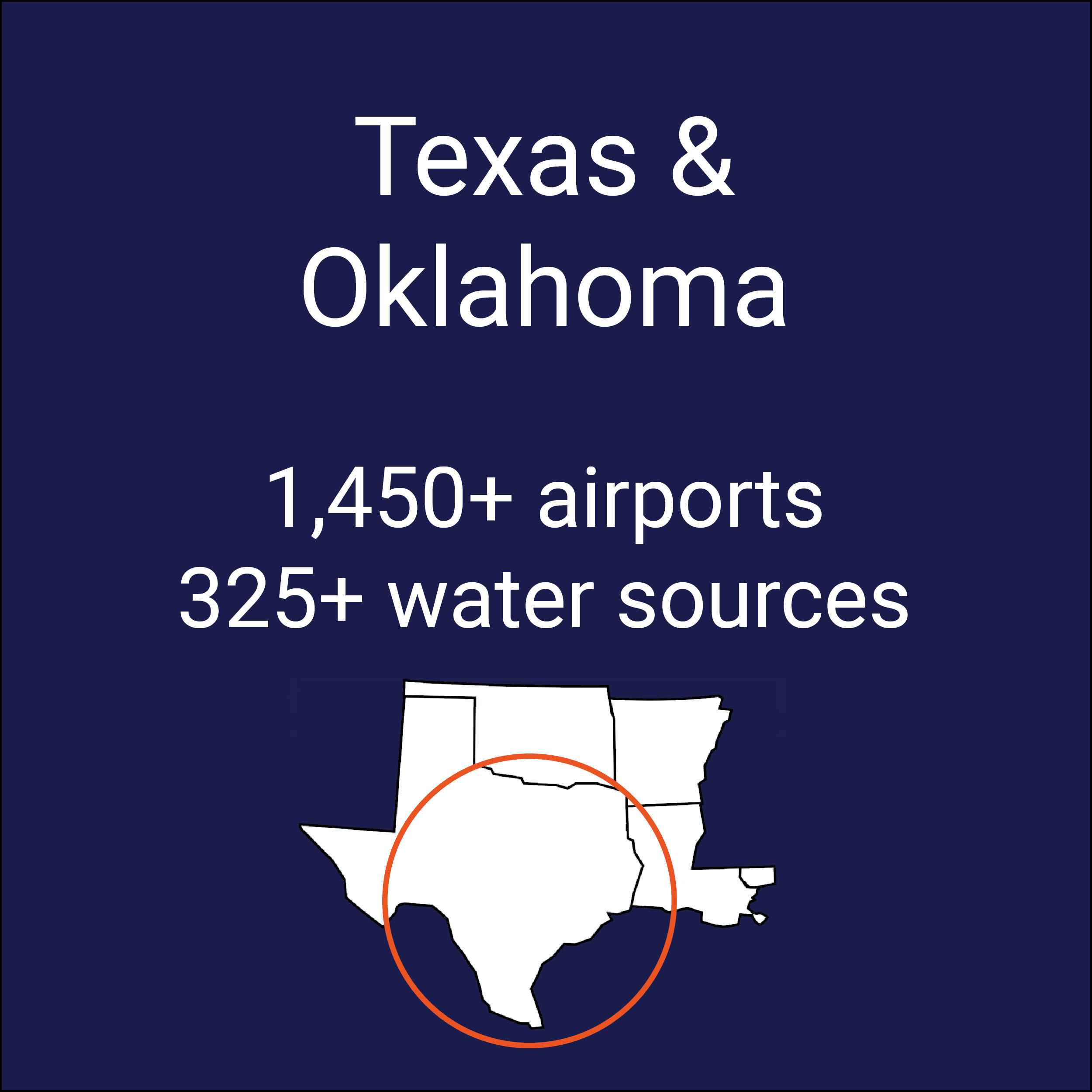

Airports and water sources are two of the key ingredients for rapid initial attack. Airports allow firefighting planes and helicopters to be stationed throughout wildfire-prone regions. Lakes, basins and other bodies of water give the planes and helicopters a seemingly endless supply of water from which they can refill their tanks.

In the US, there are more than 5,000 airports and landing strips west of the Mississippi that can support small, rapid initial attack aircraft. Historically, two-thirds of all US wildfires have occurred within 10 miles of an aircraft-accessible body of water.

Click the images below to see the rapid initial attack opportunity in three key wildfire regions.

Rapid initial attack against wildfires benefits the country and the environment

Most importantly, putting out unwanted fires fast and early reduces the risk of wildfire destruction and devastation for individuals and communities. Beyond this immediate benefit, rapid initial attack helps to accomplish the following:

Reduces the amount of harmful wildfire smoke which is known to linger for weeks, and oftentimes months, after a wildfire, negatively affecting public health.

A study published in 2018 in the Journal of the American Health Association looked at over a million emergency room visits during the 2015 wildfires in Northern and Central California. It found that on days with more wildfire smoke, there were more ED visits for cardiovascular diseases and the risks were greatest among seniors older than 65.

The damage done by wildfire smoke is not limited to a wildfire’s immediate vicinity, either. Studies have found that smoke from wildfires can worsen air quality in places thousands of miles away from the original fire, creating even more need to minimize wildfire size and accompanying smoke.

This impact on respiratory health presents an even greater threat than usual for communities that are already at high respiratory risk due to the coronavirus.

Creates safer and less taxing work environments for wildland fighters, which is important considering the high levels of suicide and PTSD facing wildland firefighters who sign up for this dangerous and demanding job. By getting to wildfires faster and overwhelming them with constant water drops, wildfire situations become less dangerous, which is especially critical in the coronavirus era when fewer wildland firefighters may be available for deployment to any given wildfire.

Reduces the need to spend millions of taxpayer dollars on large, drawn out wildfire missions and the resulting recovery costs. Again, rapid initial attack is like a sprinkler system: Make the investment upfront so the system can provide protection at a moment’s notice.

Creates significant cost savings for states and the federal government by avoiding the costs associated with large, complex wildfires. These savings can be funneled back into public works and forest health management programs that reduce the likelihood of large wildfires in the first place (e.g., forest thinning and prescribed burns). What’s more, forest health programs create jobs which can be filled by wildland firefighters in the off-season, leading to more reliable year-round employment, reducing wildland firefighter turnover season after season, and helping to create a more experienced and fulfilled workforce.

Limits the wildfire havoc wreaked on forests and watersheds. While fire is a natural and needed part of our ecosystem, large unwanted wildfires--like the recent disasters in California--wreak havoc on forests and watersheds.

Rapid initial attack reduces the rate of the large wildfires which emit large quantities of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases that continue to warm the planet and contribute to climate change.

In addition, large wildfires have a devastating impact on local watersheds, which can take years to recover. Vegetation needs time to regrow and provide roots that retain water and help hold soil in place. Until a watershed has recovered in this way, there is increased risk for flooding and debris flow, which had a disastrous impact during California’s 2017-2018 Thomas fire, when 23 people were killed as a result of debris flow. Communities damaged and untouched by the wildfire itself all experienced the impact of the region’s destroyed watershed.

As the US wildfire environment intensifies, wildfire response strategies must be adapted and transformed to meet the challenge. To urge the US government to pursue meaningful change in how the nation fights wildfires, read and sign this petition from the National Wildfire Institute and Evergreen Magazine.

To learn more about rapid initial attack, read our vision paper.